Giant Footsteps to Follow: remembering Pope Francis’ vision for radically better life on earth

As the new Pope is announced, it is more important than ever to celebrate the way that Pope Francis led, with a strong vision for the Common Good, and the need to change Capitalism to get there.

On April 21st 2025, a giant left us. In a world increasingly fractured by nationalism, inequality, and environmental crisis, Pope Francis stood as a potent moral voice calling for a more just and sustainable economic order. His passing leaves an immense void, but also a legacy of hope which must continue to challenge the status quo.

What set Pope Francis apart was his courage to directly connect economic injustice with moral failure—rejecting the notion that markets could be divorced from ethics, and vice-versa. His critique of economic systems that prioritize profit over people catalyzed new conversations about what kind of economy and economics we truly need.

A Journey Toward the Common Good

Pope Francis's economic vision fundamentally reshaped global conversations by insisting that inequality is not just a technical failure, but a moral one. Through encyclicals like ‘Laudato Si'‘, he articulated a powerful critique that recognized the interconnectedness of our challenges:

"We are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis which is both social and environmental. Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature."

His critique of "blind faith in markets" challenged fundamental assumptions in mainstream economics about the neutrality and efficiency of market mechanisms. Where conventional economics often treats markets as natural phenomena requiring minimal intervention, Pope Francis insisted that markets are human creations that should serve human needs—a perspective that resonates with economic scholarship on the essential role of public institutions in shaping markets toward collective goals.

Our connection began when friends in Argentina messaged to let me know that he had read my book ‘The Value of Everything: making and taking in the global economy’. Not long after, I saw that he had cited it in a handwritten letter to the President of the Panamerican Judges Committee, writing:

“Regarding the economic future, the vision of the economist Mariana Mazzucato, professor at University College London, is interesting. Her book ‘The Value of Everything: making and taking in the global economy’ offers insights that I believe are helpful for thinking about what comes next.”

This recognition marked the beginning of an ongoing intellectual exchange around how to rethink value, purpose and our responsibilities to each other.

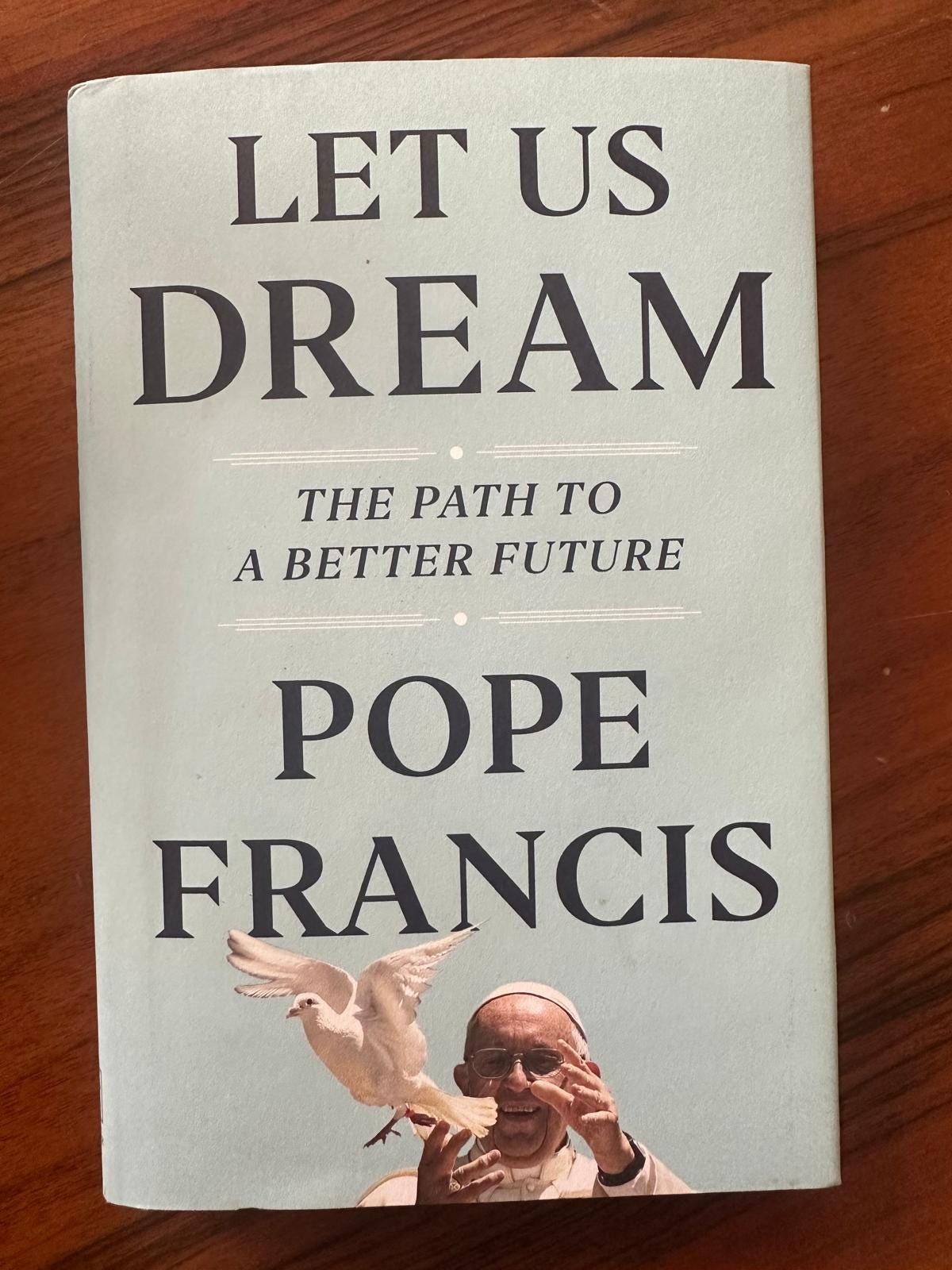

In his book ‘Let Us Dream: The path to a better future,’ Pope Francis wrote that “‘The Value of Everything’ had provoked a lot of reflection in [him]," and that it offered "a way of thinking that is not ideological, which moves beyond the polarization of free market capitalism and state socialism, and which has at its heart a concern that all of humanity have access to land, lodging and labor." I was humbled by this recognition—especially from someone so deeply committed to building bridges between ethics, economics and lived realities.

Quote (pg.64) from Pope Francis’s book, ‘Let Us Dream: The path to a better future’ (Simon & Schuster, 2020):

“Mariana Mazzucato's book ‘The Value of Everything’ provoked a lot of reflection in me. I was struck by the way that business successes lauded in our economic thinking as the result of individuals efforts or genius are in reality the fruit of massive public investment in research and education. Yet the shareholders collect vast profits, and the state is regarded as placing a burden on the market. Or I think of Kate Raworth, an economist at Oxford University, who talks of "doughnut economics": how to create a distributive, regenerative economy that moves people out of the "hole" of destitution but avoids the "ceiling" of environmental damage. Like Mazzucato, she challenges our cultures unthinking obsession with growth in gross domestic product (GDP) as the single overriding goal of economists and policymakers. I could mention others, but these two are known to me especially because of their contributions to the Vatican's thinking about a post-Covid future.

My concern is not to assess their theories–I am not qualified–but to asses the ethos of this thinking. I see ideas formed from their experience in the periphery, reflecting a concern about the grotesque inequality of billions facing extreme deprivation while the richest one percent own half of the world’s financial wealth. I see an attentiveness to human vulnerability; a desire to protect the natural world by seeing pollution as a cost that must be offset against the balance sheet. I see a concern for economies that allow all who can to access work, and that place a higher value on work that generates not just wealth for shareholders but also value for society. I see thinking that is not ideological, which moves beyond the polarization of free market capitalism and state socialism, and which has at its heart a concern that all of humanity have access to land, lodging, and labor. All of these speak to priorities of the Gospel and the principles of the Church's social doctrine. It is reasonable, then, to see this "rethinking" by women economists as a sign of our time that we should pay attention to.”

From Crisis to Transformation

The COVID-19 pandemic became a critical moment for putting these shared principles into action. Pope Francis established the Vatican COVID-19 Commission, inviting me to be a member of its Economy Taskforce, alongside the World Resources Institute, Georgetown University, Notre Dame, FaithInvest, International Labour Organization, NOW Partners and B Corp. This initiative wasn't just about recovery from crisis but, as he urged us, to ‘prepare the future’.

I led and coordinated a team that provided weekly briefings for the Pope and Vatican leadership on crucial economic responses. These briefings tackled pressing issues from debt relief to restructuring public-private partnerships, and informed several key interventions, including a piece I wrote for The New York Times on pharmaceutical profits during the pandemic. We were thrilled to hear that he mentioned our briefings during his General Audiences and during his Christmas speech on vaccinations.

Throughout this work, we were guided by a central question: what kind of economy truly serves the common good? The Commission embodied the Pope's commitment to rethinking economic and social systems to better serve those most affected by the crisis.

We're proud to now have Marcela Chapa Garza, who was the former Chief of Staff to the Secretary of the Vatican COVID-19 Commission’s Economy Taskforce, on our team as Project Manager for IIPP's Strategic Economic Alliance (SEA).

The Pontifical Academy for Life

Pope Francis's approach to dialogue was transformative—he was relentless in bringing diverse perspectives together, widening the pool of contributors to the Vatican’s mission. This desire to seek out new allies led to my appointment to the Pontifical Academy for Life, an institution dedicated to advancing human dignity at the intersection of ethics, science, and society. By broadening the Academy's focus to include economists and policy experts, Pope Francis made clear that conversations about life must include the structures—economic, social, and technological—that shape how we live.

Some conservative Catholic media outlets questioned whether someone with my personal views on women’s reproductive rights should serve on the Academy. When asked about this during a press conference returning from Bahrain in November 2022, Pope Francis responded with characteristic directness and warmth:

"Women know how to find the right path, they know how to move forward. And now I have put Mariana Mazzucato in the Pontifical Academy for Life. She is a great economist... I put her in to give a little more humanity to this."

These words exemplify his leadership style: humble, courageous, and unafraid to build coalitions across traditional boundaries. Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia similarly defended the appointment, explaining that the Academy includes diverse backgrounds specifically to foster "interdisciplinary, intercultural, and inter-religious dialogue."

During my first Vatican visit for the Academy's assembly on ‘Human: Meanings and Challenges,’ I addressed these criticisms directly, emphasizing that my academic work has never focused on abortion or religion: "I'm an academic, I'm an economist, I've never written an op-ed, a blog, a journal article or a book that has had even the word 'abortion' or 'religion' in it." What connects my work to Pope Francis's vision is a shared focus on redesigning the economy so that it's good for humanity, particularly for the billions lacking access to essential services like healthcare and clean water.

"Wouldn't it be great if your paper, and all papers and all journalists in the world had real curiosity to talk to biologists, physicists, poets, economists, with urgency and said what will you do, how will you help us – not asking an economist what she thinks about abortion," I remarked. I reminded those present that my work focuses on "redesigning the economy so that it's good for humanity," addressing critical issues like the 4.5 billion people lacking access to essential health services and the 2 billion without safely managed water. This focus on improving life on earth for the most people in the world is what connected me to Pope Francis's vision.

Since then, the work we have done with the Pontifical Academy for Life has spanned topics ranging from artificial intelligence to inclusive global governance. These collaborations eventually brought us together in person, after years of mutual admiration and alignment in purpose. At the heart of it all is a shared commitment to putting the economy in the service of life—and not the other way around.

During the same visit, I had the opportunity to speak at a Vatican event where we discussed how the Pope's framework of "fraternity" has implications for economic theory. As I noted then, "The Pope speaks about the common good much more than economists do," highlighting how his approach moves from the traditional economic theory of market failure toward a more ambitious vision of marketing creation that centers human needs rather than abstract principles.

An Economics of the Common Good Takes Shape

The culmination of our shared intellectual journey came last November in 2024, when I convened a dialogue at the Vatican with Prime Minister Mia Mottley of Barbados and Pope Francis on ‘An Economics of the Common Good: Theory and practice.’ For this historic event, Pope Francis prepared a special written message that specifically highlighted the significance of having women lead the conversation:

"The second reason I would like to highlight is that at this event, two women with different responsibilities and backgrounds will be present. We need, in society as in the Church, to listen to female voices; we need diverse forms of expertise to cooperate in the formulation of an extensive and wise reflection on the future of humanity; we need all world cultures truly to be able to offer their contribution and express needs and resources."

This conversation focused on how a new economics of the common good could help address our interconnected global crises—climate, biodiversity, water, and health. In his message, Pope Francis further emphasized:

"The quest for the common good and justice are central and indispensable aspects of any defence of every human life, especially the most fragile and defenceless, with respect for the entire ecosystem we inhabit."

He noted that:

"We need solid economic theories that take on and develop this theme [of the common good] in detail, so that it can become a principle that effectively inspires political choices... and not merely a category much invoked in words but disregarded in deeds."

Perhaps most tellingly, he wrote:

"Universal fraternity is, in some way, a 'personal', warm way of understanding the common good. Not simply an idea, a political and social project, but rather a communion of faces, histories, people. The common good is first and foremost a practice, made up of fraternal welcome and a common search for truth and justice."

An economics of the common good represents a fundamental departure from conventional economic frameworks that focus primarily on correcting "market failures." Instead, it recognizes that markets themselves are outcomes of how we organize economic activity, and that they should be deliberately shaped to serve collective needs. This approach demands that we evaluate economic arrangements not merely by efficiency or growth metrics, but by how well they enable all people to flourish while respecting planetary boundaries. It calls for new measurement tools beyond GDP, new governance structures that prioritize long-term collective welfare, and new models of public-private collaboration that share both risks and rewards.

The Pope was more rigorous than most economists when he talked about the common good: not as a correction but as an objective, with principles to guide it. Principles like the “preferential option for the poor” (making sure that all policies evaluate how the most vulnerable are affected first) and the “principle of subsidiarity” (paying attention to the lived experience on the ground) were in his view key pillars to build the Common Good.

As I discussed in my recent Substack ‘Why We Need an Economics Grounded in the Common Good,’ which builds on my academic work, ‘Governing the Economics of the Common Good’ (2024), this economics of the common good must not be a correction for a market failure but an objective to reach, where the how matters as much as the what. In the article I discuss five pillars: purpose and directionality; co-creation and participation; collective learning and knowledge-sharing; access for all and reward-sharing; and transparency and accountability. These principles can guide us in addressing our most urgent global challenges, from climate change to healthcare–as I describe in the clip below, filmed on my last visit to the Vatican in November 2024.

Building Bridges for Systemic Change

Pope Francis's legacy lies not only in what he critiqued, but in whom he invited to the table. He was a restless advocate for listening to the people in the existential peripheries and built bridges with diverse realities. His approach to dialogue across traditional boundaries exemplified his belief that addressing complex global challenges requires diverse perspectives.

In an era of increasing nationalism and withdrawal from global cooperation, as I recently discussed in my Substack on ‘The Trump Vacuum,’ Pope Francis remained a steadfast advocate for multilateralism and global solidarity. He understood that our interconnected crises demand collective action across borders, and he created spaces for meaningful dialogue between those most affected by these crises and those with the power to address them.

Carrying Forward His Vision

The vision Pope Francis articulated has already begun to take concrete form through initiatives like the Jubilee Commission on Addressing the Debt and Development Crises, established by the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and chaired by Joseph Stiglitz, with the leadership of experts including Martín Guzmán, and to which I contribute as an advisor. The Commission is working to ensure that global debt architecture enables countries to prioritize health, education, and green transitions—putting the common good above creditor interests.

As we move forward without Pope Francis's physical presence, his moral clarity and willingness to challenge entrenched systems continue to guide us. The new economics–what I would call an economics of the common good–he championed—focused on solidarity, sustainability, and human dignity rather than narrow metrics of growth—remains our most promising path for addressing the existential challenges of our time.

A giant has indeed left us, but his vision continues to illuminate the way forward. May he rest in peace.

Further reading:

Francis. (2015). Laudato si': encyclical letter. Vatican Press.

Francis. (2020). Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future. Simon & Schuster.

Mazzucato, M. (2020). Drug Companies Will Make a Killing From Coronavirus. The New York Times. March 18.

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (2020). Stakeholder Capitalism During and After COVID-19. UCL IIPP COVID-19 Briefing Papers 01. April.

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (2020) Inequality, Unemployment and Precarity, UCL IIPP COVID-19 Briefing Papers 02. May.

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (2020) Reshaping Global Health Systems in Response to COVID-19, UCL IIPP COVID-19 Briefing Papers 03. June.

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (2020). A Green Economic Renewal After the COVID-19 crisis. UCL IIPP COVID-19 Briefing Papers 04. June.

Mazzucato, M. (2024). Governing the Economics of the Common Good: From correcting market failures to shaping collective goals. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 27(1), 1-24.

Mazzucato, M. (2025) The Trump Vacuum: How Brazil and South Africa have the opportunity to reshape the global order. Mission Economics.

Why We Need an Economics Grounded in the Common Good

As we close 2024, we find ourselves living through what my friend and Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Mottley calls "the season of superlatives" – a year marked by record-breaking extremes: the hottest global temperatures, the most devastating floods, the worst droughts. These records are not just statistics - they are symptoms of our failing economic sy…