On Tuesday, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves outlined her growth strategy for the UK, presenting a vision for turning the country into "Europe's Silicon Valley." To create genuine innovation ecosystems, we need to understand what made Silicon Valley successful in the first place. As I outline in my 2013 book “The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking public vs. private sector myths”, it wasn't just about reducing barriers - it was about decades of strategic, decentralized and entrepreneurial public investments actively shaping and creating markets.

Reeves is correct: the UK has historically underinvested compared to its peers. Public investment has averaged just 2.6% of GDP over the last 25 years versus the G7 average of 3.5% and OECD average of 3.7%. The scale of this underinvestment is stark: if the public sector had matched the G7 average between 2006 and 2021, the British government would have invested an additional £208.4 billion in real terms.

This chronic underinvestment isn't limited to the public sector. The UK has ranked last in G7 private investment for 24 of the last 30 years, and in 2022 was behind all G7 countries for the third consecutive year. Had UK business investment merely remained at the G7 median level since 2005, the private sector would have invested an additional £354.3 billion by 2021 in real terms. While the UK has now reached the OECD average of 2.7% for gross domestic expenditure on R&D, we can and must do better to emulate Silicon Valley's success. Tax breaks alone aren't enough - currently, the UK provides about twice as much tax relief as direct funding for business R&D.

Mainstream economics often claims that public-sector finance 'crowds out' private investment. But evidence shows the opposite: ambitious government investments–when designed well–can generate additionality, creating activity that wouldn't otherwise occur. Recent examples from the US make this clear. Since the introduction of the Inflation Reduction Act, companies have announced more than $242 billion in private clean energy investments. Similarly, the CHIPS Act has catalyzed over $157 billion in private semiconductor investments. These results demonstrate how strategic public funding crowds in private capital at scale.

Public funding can be made conditional on business investment in areas like R&D, helping to de-financialize businesses that attempt to reap profits without real investment. But without the right institutions, it will be hard for the UK to compete with the US and China. We have relatively weak public financial institutions - nowhere near the scale of Brazil's BNDES or Germany's KfW (which we wrote about in our report on Mission-oriented Development Banks). Compare Germany's Fraunhofer system (€3.4bn/year, 32,000 staff, 76 centers) with the UK's Catapult network (£1.6bn over 5 years). Real innovation ecosystems need sustained funding and institutional networks that connect research to markets.

In Scotland, our work at the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose tried to bring some of the lessons in through A Mission-oriented Framework for Scotland's National Investment Bank, which we helped establish in 2020 with £2 billion of government funding. The framework shows how public investment catalyzes innovation in three ways: providing patient strategic finance, overcoming coordination failures between innovation actors, and signaling future market opportunities to businesses.

An entrepreneurial state isn't about top-down direction - it's about dynamic networks catalyzing innovation across entire value chains. Reeves' ambition to reinvigorate British innovation is a step in the right direction. If there is to be a ‘European Silicon Valley, it will come from investment in distinctive innovation capabilities to solve 21st century challenges. This means patient, mission-oriented public investment focused on today's grand challenges - from net zero to health inequality. Just as the examples of US defense spending and public research created the foundations for Silicon Valley's later success, the UK's path to becoming an innovation leader will require sustained state investment and an entrepreneurial state working in partnership with business to shape and create new markets.

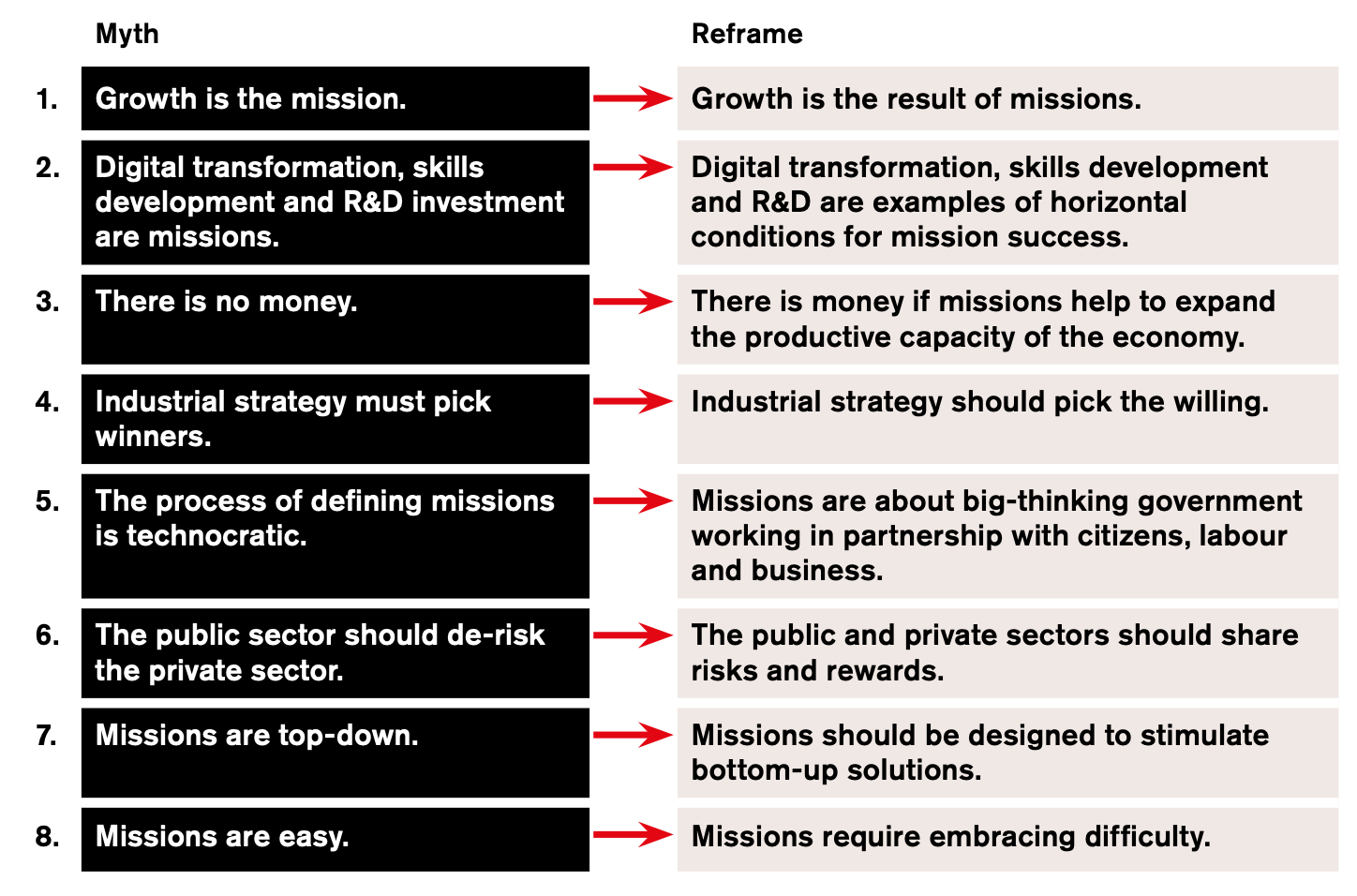

The way innovation happens - through collective, cumulative and uncertain processes - requires us to fundamentally rethink public-private partnerships. A mission-oriented approach provides the framework: setting ambitious directions while enabling bottom-up experimentation across sectors to achieve concrete goals. This means moving from seeing growth as the mission to understanding growth as the result of the investment and innovation required for solving missions; from picking winners to picking the willing; from merely de-risking private investment to sharing both risks and rewards fairly between public and private actors.

As we outline in Mission-oriented Industrial Strategy: Global insights (co-authored with Sarah Doyle and Luca Kuehn von Burgsdorff), we need to learn the lessons of innovation of the past, we need to move away from old myths about the role of the state that stifle industrial strategy and reframe our understanding of how public and private sectors can work together to create markets ex-ante, not just fix them ex-post.

Further reading:

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking public vs. private sector myths. London: Anthem Press.

Mazzucato, M. (2014). A Mission-oriented Approach to Building an Entrepreneurial State. InnovateUK. Policy Report.

Mazzucato, M. and MacFarlane, L. (2023). Mission-oriented Development Banks: The case of KfW and BNDES. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Policy Report.

Mazzucato, M. and Rodrik, D. (2023). Industrial Policy with Conditionalities: A taxonomy and sample cases. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2023-07).

Mazzucato, M., Doyle, S. and Kuehn von Burgsdorff, L. (2024). Mission-oriented Industrial Strategy: Global insights. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, IIPP Policy Report No. 2024/09.

The social contract can evolve to the social partnership. It must empower people as well as share snd distribute the rewards fairly. More Mutual Equity, more employee ownership more dispersed power, decision making and wealth creation and sharing. A new economics, a new financial system a new peak experience in the words of Maslow.